The French and the Greek Revolution

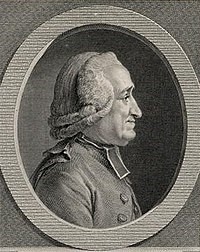

Swazel-Guffier was a student of the archaeologist and writer Jean-Jacques Barthélemy, who also inspired Riga Feraios in his work on the Charter.

But many other French scientists also contributed important work to Greece.

The paper of the Journal des Debats (The Journal of Public Debates) of August 31, 1821, refers to the work of the great French geographer, Malte-Brun, who recorded in detail the geography and all the population data of the Peloponnese.

Thus, at the beginning of the 19th century, a climate of love for Greece and the Greeks suffering in the Ottoman Empire developed in public opinion, which systematically received an extremely Greek-centric education. This climate dominates the arts and then passes into politics. An indicative example is the proposal to the Parliament of 1816, by the politician and great Philhellene Satovriandos, in favor of the abolition of the slavery of Christian populations.

This proposal, which was voted in favor, refers to the rights of humanity and the erasure of shame in Europe. The scourge of slavery and the abduction of Christians by Turks was depicted in many ways in art. However, Satovriandos owes the title of Philhellenic mainly to the famous "Memorandum on Greece" (Note sur la Grėce, 1825), which was a Philhellenic manifesto during the Revolution.

From the moment the Greek Revolution became known in Western Europe, newspapers began to be flooded daily with news of military operations and political developments.

The French newspaper La Quotidienne (The Daily) of June 12, 1822, refers for example to massacres of Greeks by Turks, announces the liberation of Athens, etc. The particularly important element is that this authoritative newspaper, for the first time, uses the term "Greece » to refer to the Peloponnese and Sterea that the Greeks have liberated.

Another sheet of the French newspaper Gazette de France (The Gazette of France) of January 16, 1827, refers to the French officer Faviero and other Philhellenes who were fighting in Attica.

While the sheet of June 15, 1827, describes the negotiations of the French commander De Rigny, with Rachid Pasha for the protection of the Athenians.

This intense interest in the Revolution of 1821 was also reflected in literature.

Since 1821, more than 2000 philological works (poems, plays, pamphlets of historical and political content, etc.) referring to the Greek Revolution, which were praised by well-known poets of the time, were written and circulated internationally. Like the academics Guiraud and Casimir Delavigne, Victor Hugo and Alphonse de Lamartine.

We stand on two occasions concerning Messolonghi, which showed the public opinion of Europe that the epic and heroic Greece of Thermopylae was still alive. A letter from the Italian composer Pacini (who lived permanently in Paris) is indicative. With it, he offers the proceeds from the sale of his musical work for Messolonghi instead of one franc per copy, so that the money will go to the Hellenic Charity Commission, as well as its response.

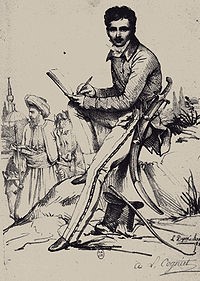

A large number of painters realized a series of works in oil, paper, metal or tapestry, showing fighters of 1821, scenes of conflict between Greeks and Turks, Greek refugees, oath and departure of a Greek fighter, etc.

Its members also included Greeks living in Paris, such as Adamantios Korais. The committee organized fundraisers to which famous people contributed, as well as ordinary people.

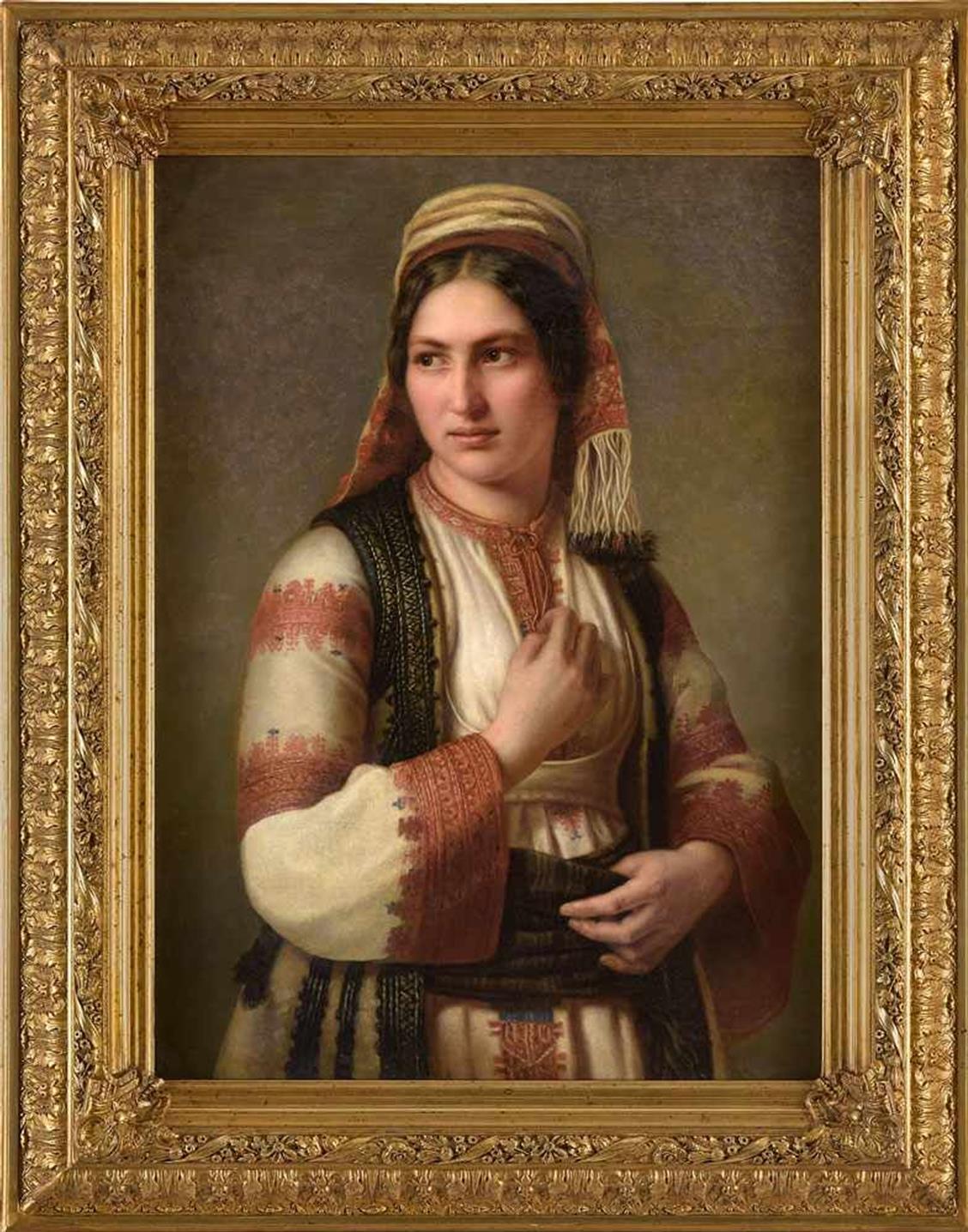

In February 1825, the "Charitable Committee in favor of the Greeks" was founded in Paris. A new philhellenic organization with much broader goals, which aimed to raise money through fundraisers to help the Greeks and the military. At the same time, the "Society of Christian Ethics" continued to help, especially in the field of education, undertaking the education of orphaned Greek children in France and sending its member and eminent educator Dutrone to Greece, to offer his services in the organization of schools . In the exhibition you can see a particularly iconic painting depicting the young son of the arsonist Canaris in Paris being educated by a scholar.

A similar Philhellenic movement was observed in other cities. As in Marseille, Lyon and Strasbourg.

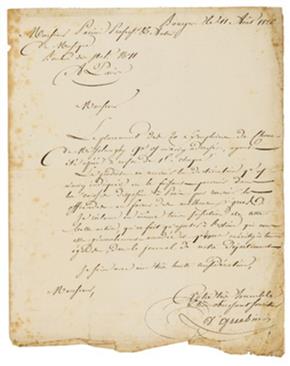

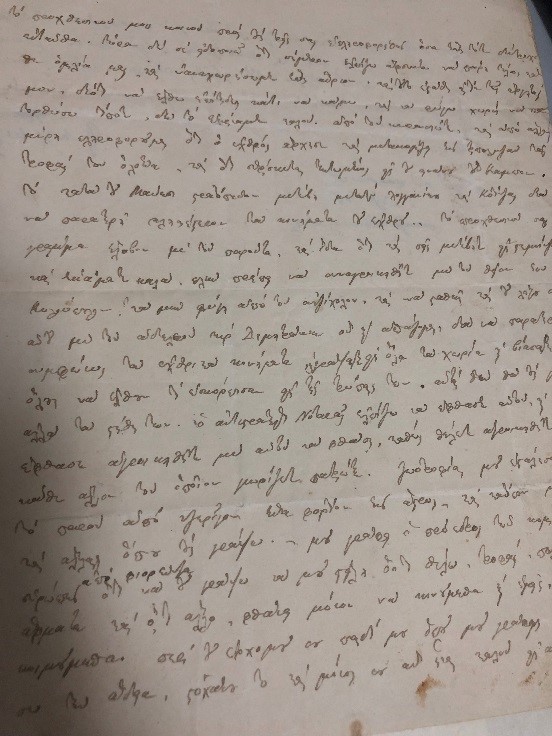

The committees, and many officials of the French government were in constant contact with the Greeks. The following is a letter of 1824 from Dimitrios Ypsilantis to the Minister of Justice of France, from whom he requests the support of the French government. In fact, Ypsilantis had as a close associate the French philhellene Olivier Boutier, who fought as a colonel, and then a general, of the Greek army in the occupation of Tripoli and Athens, and helped in the use of artillery.

Many types of porcelain dinnerware with a corresponding abundance of illustrations. Decorative vases and porcelain figurines, storage boxes, but also board games and fans with philhellenic themes used by ladies in France. You can see all this in the exhibition.

Of particular interest is a commemorative philhellenic fan from the April 28, 1826 concert at the Vauxhall in Paris, which was a peak moment of the philhellenic movement in France and was characterized as the most secular event of the time. All the well-known ladies of the aristocracy then took the stage and sang for the sake of the Greek people. One side of the fan reads 'Cantate chantée au concert du Vauxhall', and the inscription: 'A la Patrie. Mourons pour la défendre et vivons pour l’aimer”. On the left a flag with a cross and on the right a horn of Amalthea from which flows the income from the generous offerings of the Philhellenic people. The other side shows the names of the contributors.

The action of the Philhellenes is recorded in a particularly important letter sent by Theodoros Kolokotronis to his son Ioannis on July 8, 1826, and among other things he mentions "... the president of the committees of Europe writes to me to write to him to send me what I want, food, tanks and everything else, it's enough that we move and not sleep...".

Establishment of the first philhellenic committee.

In France, the first Philhellenic committee was founded in Paris at the beginning of 1823, within the "Society of Christian Ethics", under the name "Committee in favor of Greek refugees in France". Among the members of the committee were distinguished figures of public life, of liberal persuasions, such as its president, the Duke de la Rochefoucault-Liancourt, the Duke de Broglie, and the two senators, as well as deputies and bankers.

Its members also included Greeks living in Paris, such as A. Korais, K. Schinas, A. Vogoridis and D. Fotilas. The committee, according to its objectives, would make efforts for the treatment and channeling of refugees to Greece who had taken refuge in France after the Turkish massacres in Asia Minor and Chios, and for this purpose organized fundraisers, to which well-known persons contributed of the time, but also ordinary people.

Σχόλια