First Sunday of Lent (Feast of Orthodoxy)

Doctrinal causes and the first restoration

There were various reasons for launching a war against the icons, with Emperor Leo III as the prime mover and his son, Constantine V, a relentless defender. But her main argument was of a spiritual and doctrinal nature, specifically the danger of idolatry to which the faithful were led by the worship of the depiction of holy persons and the relics of the saints, with the deviation of the performance of worship from the archetype, i.e. God and his Saints, in their visual representation and the wood of the image itself. For the iconoclasts, the only acceptable image of Christ is that of his "animal body", which is present in the Holy Eucharist, and which, together with the sign of the cross and the church space, constitutes the believer's only channel of spiritual communication with God.

I mention in passing that, although in the 8th century the establishment of icons and their worship had become general, objections to the doctrinal subject of the representation of God the Word had already been expressed in the 4th century by Eusebius of Caesarea and even in the 7th century and at the beginning of 8th by certain bishops of Phrygia and Cappadocia.

The restoration of images and the crystallization of doctrine

The 7th Ecumenical Council, which restored the honor of icons, based on the theological texts of John Damascene, clarified the formal function of icons as a bridge of spiritual communication between the believer and the archetype of the icon, who (must) be the only recipient of his worship: "... the septa and the holy icon are placed in the holy churches of God... and ... they give the same apocalypse and honorable worship, not the true worship according to our faith, which should only be given to the divine nature... Because the icon honors the original passes through and the one who worships the image worships in it the existence of the written one".

Putting an end to the iconoclastic period, the synod of 843 essentially put an end to the Christological disputes, that is to say the debates and heretical positions regarding the existence, the two natures of Christ and the mystery of the divine incarnation, which from the 4th century the Church, with the support of the emperors, he had to face and fight, progressively formulating, through theological debates and the decisions of seven ecumenical councils, the orthodox doctrine as we advocate and preach it today.

Thus, if the veneration of images is ultimately identified with the very concept of Orthodoxy, i.e. correct doctrine/correct faith, it is because it summarizes the recognition of the fundamental theological doctrine of the incarnation of the Lord and of his inseparable and indivisible divine-human nature: as a perfect man that existed, the "virtual reproduction" of his human form, and by extension that of the Saints, the athletes of the faith, is possible and desirable, "it is acceptable and pleasing in the sight of God". Conversely, the denial of the figurative representation of the Lord is equivalent to a denial of the theology of his incarnation and its salvific significance for man.

Henceforth, any suggestion of questioning the worship of icons or a philosophical approach to the divine-human nature of Jesus Christ was treated as a serious threat to the stability and peace of the empire itself and therefore immediately condemned. Thus, the Synodikon of Orthodoxy, which includes the decisions of the seven ecumenical councils of the Church and the nominal condemnation of heretics who questioned the doctrine, was still completed in the 11th and 12th centuries and for the last time in the 14th century (quiet schism) with the excommunication of those whose teaching, writings, or activity were deemed heretical and therefore worthy of anathema.

The image of Orthodoxy

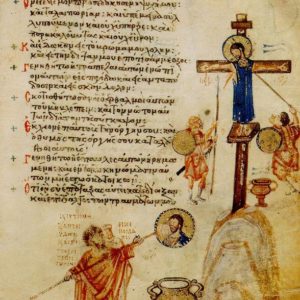

Contrary to what one might expect, the icon entitled "Orthodoxy" appeared in Christian art only six centuries later (!), and more precisely in the middle of the 15th century. The oldest surviving specimen from the Byzantine period, currently kept in the British Museum, can be dated after 1436 .

The pictorial composition is organized into two horizontal zones, each around a central image surrounded by two distinct groups of believers. In the upper zone, in the center, two attendant angels flank an image of the Virgin Mary, placed on a pedestal covered with a heavy embroidered fabric. On the left, empress Theodora and her minor son, Michael III, and on the right, the patriarch Methodios, a bishop and two monks, whose names have been erased, stand reverently. The lower zone of the composition depicts the Holy Confessors (of the faith), eleven defenders of icons who were persecuted or martyred during the iconoclasm period. Among them, in the center, Theodore the Studite and Theophanes the Confessor, holding between them an icon of Christ, the brothers Theodore and Theophanes Graptos, Saint John and, on the left, Saint Theodosia, holding an icon.

In the Paleologian period, the worship of the Grapta brothers, of St. Ioanniki and especially of Agia Theodosia, who according to tradition was martyred in 729, trying to prevent the removal of the image of Christ from the door of the palace by order of the emperor, experienced a resurgence. More specifically, the revival of the veneration of the saint was connected with her miraculous intervention, in 1436, in the healing of the old patriarch Joseph II (1416-1439), so that her presence in the image is a criterion for dating this pictorial subject.

The historical and political context

The timing of the appearance of the image in combination with the depicted persons makes it clear that the character of the composition is not commemorative or celebratory of the historical event of the 9th century, but that it is inscribed in the climate of the spiritual and social crisis caused by the Caesar-papal policy of the Palaiologan emperors advocating the union of the Eastern and Western Churches: if the Union was the only hope of the Paleologues to secure the alliance of the Pope against the conquering ambitions of the Latin monarchs, and later of the Ottomans, the clergy and people of Byzantium were determined not to yield to the demands of the Catholic pontiff, who demanded submission of the Eastern church to his authority. Apart from the doctrinal and liturgical differences that separated the two Churches, the suspicion, if not the hostility, of the people towards the Westerners after the fall of Constantinople in 1204, weighed heavily on the intransigent attitude of the antithetical majority.

On the eve of the Ferrara-Florence Council (1437-1441), in which John VIII Palaiologos based his last hopes for a common defense of the Christian world against Islam, in return for the submission of the Church of Constantinople to the Church of Rome, the Ottomans were already at the gates of Vasilevousa. In this context, the composition of the image of Orthodoxy projects as a banner of confession of faith.

It sounds like a call for sympathy and collaboration of political and ecclesiastical power for the defense of the Orthodox doctrine, like the Empress Theodora and the Patriarch Methodios in the past.

He reminds the members of the Byzantine mission in Ferrara - headed by the antithetical patriarch Joseph II, who was healed by Saint Theodosia - that the struggles and sacrifices of her Saints supported the spiritual prestige of the thousand-year historical course of the Eastern Church.

And it would perhaps not be an exaggeration to say that it proclaims Orthodoxy as a symbol of the historical, spiritual and cultural identity of a "Byzantine" nation in the making.

Hellas

Today, in commemoration of the restoration of the icons, the Sunday of Orthodoxy is celebrated in all Orthodox Christian churches during the first Sunday of Lent, i.e. 42 days before Easter. During the liturgy, a passage from the letter to the Hebrews (1:24-26, and 32-40) is read, where the struggles of the holy men of the Old Testament in favor of faith are set forth, as well as a passage from the Gospel of John (1 40 AD), where the call of Philip and Nathanael who confessed Jesus Christ as the son of God is told: "Lord, you are the son of God, you are the King of Israel".

In Greece, the Creed#The Creed of Nicaea-Constantinople is normally recited by the cantors at the Divine Liturgy, but on Orthodox Sundays it is recited by a lay member of the church who is a state official. It is an honorary privilege offered to the head of state, in continuation of the same privilege possessed by the Emperors. From the reign of George I, it was well established that the King - and today the President of the Republic - would come to the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens and recite the I Believe.

In 2024, the Permanent Holy Synod of the Church of Greece, decided that the celebration would not take place in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens, but in the Petraki Monastery, as well as not attending the established meal at the Presidential Palace. The development was interpreted as a reaction of the Orthodox Church to the passing of the law on the marriage of same-sex couples and the positive attitude of the President of the Republic, Katerina Sakellaropoulou.

Russia

The ceremony, as it had been used in the Russian Empire, differed from the Emperor and his family, and the "Eternal Memory!" proclaimed for every member of the Romanov dynasty. All who denied "the divine right of kings and all who dared to raise rebellion and sedition against them" were anathema. Anathemas against Modernism and Ecumenism have been added to the Russian Orthodox Church outside of Russia.

Theological significance

The name of this Sunday reflects the great importance that icons have for the Orthodox Church. They are not optional liturgical add-ons, but an integral part of Orthodox faith and devotion. The debate included important issues: the character of Christ's human nature, the Christian attitude toward matter, and the true meaning of Christian redemption. The icons are considered by the Orthodox as a necessary consequence of the Christian faith in the Incarnation of the Word of Jesus, (Evangelion of John 1:14). Icons are considered by Orthodox Christians to have a sacramental character, giving the believer the person or event depicted in them. However, the Orthodox always make a clear doctrinal distinction between the pilgrimage attributed to images and the worship due to God alone.

Σχόλια