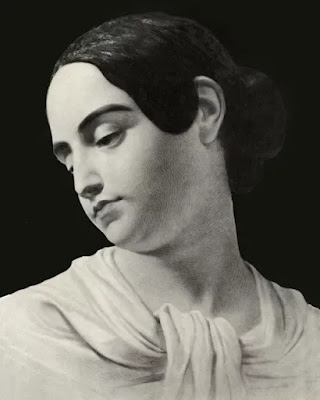

Edgar Allan Poe: The lover of the ancient Greek spirit

He was a fanatical admirer of the ancient Greek spirit and dreamed of traveling to Greece. In each of his texts there was some reference or some Greek word. The reason for the "dark" Edgar Allan Poe.

Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston in 1809, to theatrical parents. Before he was two years old, his parents died, and Edgar found himself in Richmond, in the home of the merchant John Allan, who, however, never adopted him. His relationship with his stepfather was never good, but it worsened when Allan forced Edgar to drop out of the University of Virginia because he was unwilling to pay his own expenses. In 1830 Edgar entered the Military Academy at West Point, from which he was expelled the following year, deliberately causing a scandal to avenge his stepfather.

He then worked for a long time on various newspapers in Richmond, Philadelphia, and New York, for the sake of a living, but at the same time gaining a reputation as an authoritative critic. "The Crow and Other Poems", published in 1845, established him overnight as a writer, but did not relieve him of the poverty in which he had lived all his life. In 1836 he married his fourteen-year-old cousin Virginia, who died of tuberculosis eleven years later. He died in 1849, an alcoholic and opium addict constantly chasing a vision of the lost Virginia, and was buried next to her in Baltimore, as he had wished.

Edgar Allan Poe (né Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, author, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is widely regarded as a central figure of Romanticism and Gothic fiction in the United States, and of American literature. Poe was one of the country's earliest practitioners of the short story, and is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre, as well as a significant contributor to the emerging genre of science fiction. He is the first well-known American writer to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career.

Poe was born in Boston, the second child of actors David and Elizabeth "Eliza" Poe.[ His father abandoned the family in 1810, and when his mother died the following year, Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan of Richmond, Virginia. They never formally adopted him, but he was with them well into young adulthood. He attended the University of Virginia but left after a year due to lack of money. He quarreled with John Allan over the funds for his education, and his gambling debts. In 1827, having enlisted in the United States Army under an assumed name, he published his first collection, Tamerlane and Other Poems, credited only to "a Bostonian". Poe and Allan reached a temporary rapprochement after the death of Allan's wife in 1829. Poe later failed as an officer cadet at West Point, declared a firm wish to be a poet and writer, and parted ways with Allan.

Poe switched his focus to prose, and spent the next several years working for literary journals and periodicals, becoming known for his own style of literary criticism. His work forced him to move between several cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City. In 1836, he married his 13-year-old cousin, Virginia Clemm, but she died of tuberculosis in 1847. In January 1845, he published his poem "The Raven" to instant success. He planned for years to produce his own journal The Penn, later renamed The Stylus. But before it began publishing, Poe died in Baltimore in 1849, aged 40, under mysterious circumstances. The cause of his death remains unknown, and has been variously attributed to many causes including disease, alcoholism, substance abuse, and suicide.

Poe and his works influenced literature around the world, as well as specialized fields such as cosmology and cryptography. He and his work appear throughout popular culture in literature, music, films, and television. A number of his homes are dedicated museums. The Mystery Writers of America present an annual Edgar Award for distinguished work in the mystery genre.

Edgar Poe was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1809, the second child of American actor David Poe Jr. and English-born actress Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe. He had an elder brother, Henry, and a younger sister, Rosalie. Their grandfather, David Poe, had emigrated from County Cavan, Ireland, around 1750.

His father abandoned the family in 1810, and his mother died a year later from pulmonary tuberculosis. Poe was then taken into the home of John Allan, a successful merchant in Richmond, Virginia, who dealt in a variety of goods, including cloth, wheat, tombstones, tobacco, and slaves. The Allans served as a foster family and gave him the name "Edgar Allan Poe", although they never formally adopted him.

The Allan family had Poe baptized into the Episcopal Church in 1812. John Allan alternately spoiled and aggressively disciplined his foster son. The family sailed to the United Kingdom in 1815, and Poe attended the grammar school for a short period in Irvine, Ayrshire, Scotland, where Allan was born, before rejoining the family in London in 1816. There he studied at a boarding school in Chelsea until summer 1817. He was subsequently entered at the Reverend John Bransby's Manor House School at Stoke Newington, then a suburb 4 miles (6 km) north of London.

Poe moved with the Allans back to Richmond in 1820. In 1824, he served as the lieutenant of the Richmond youth honor guard as the city celebrated the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette. In March 1825, Allan's uncle and business benefactor William Galt died, who was said to be one of the wealthiest men in Richmond, leaving Allan several acres of real estate. The inheritance was estimated at $750,000 (equivalent to $19,000,000 in 2022). By summer 1825, Allan celebrated his expansive wealth by purchasing a two-story brick house called Moldavia.

Poe may have become engaged to Sarah Elmira Royster before he registered at the University of Virginia in February 1826 to study ancient and modern languages. The university was in its infancy, established on the ideals of its founder, Thomas Jefferson. It had strict rules against gambling, horses, guns, tobacco, and alcohol, but these rules were mostly ignored. Jefferson enacted a system of student self-government, allowing students to choose their own studies, make their own arrangements for boarding, and report all wrongdoing to the faculty. The unique system was still in chaos, and there was a high dropout rate. During his time there, Poe lost touch with Royster and also became estranged from his foster father over gambling debts. He claimed that Allan had not given him sufficient money to register for classes, purchase texts, and procure and furnish a dormitory. Allan did send additional money and clothes, but Poe's debts increased. Poe gave up on the university after a year but did not feel welcome returning to Richmond, especially when he learned that his sweetheart Royster had married another man, Alexander Shelton. He traveled to Boston in April 1827, sustaining himself with odd jobs as a clerk and newspaper writer, and started using the pseudonym Henri Le Rennet during this period.

Military career

Poe was unable to support himself, so he enlisted in the United States Army as a private on May 27, 1827, using the name "Edgar A. Perry". He claimed that he was 22 years old even though he was 18. He first served at Fort Independence in Boston Harbor for five dollars a month. That year, he released his first book, a 40-page collection of poetry titled Tamerlane and Other Poems, attributed with the byline "by a Bostonian". Only 50 copies were printed, and the book received virtually no attention. Poe's regiment was posted to Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina, and traveled by ship on the brig Waltham on November 8, 1827. Poe was promoted to "artificer", an enlisted tradesman who prepared shells for artillery, and had his monthly pay doubled. He served for two years and attained the rank of Sergeant Major for Artillery, the highest rank that a non-commissioned officer could achieve; he then sought to end his five-year enlistment early. He revealed his real name and his circumstances to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Howard, who would allow Poe to be discharged only if he reconciled with Allan. Poe wrote a letter to Allan, who was unsympathetic and spent several months ignoring Poe's pleas; Allan may not have written to Poe even to make him aware of his foster mother's illness. Frances Allan died on February 28, 1829, and Poe visited the day after her burial. Perhaps softened by his wife's death, Allan agreed to support Poe's attempt to be discharged in order to receive an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.

Poe was finally discharged on April 15, 1829, after securing a replacement to finish his enlisted term for him. Before entering West Point, he moved to Baltimore for a time to stay with his widowed aunt Maria Clemm, her daughter Virginia Eliza Clemm (Poe's first cousin), his brother Henry, and his invalid grandmother Elizabeth Cairnes Poe. In September of that year, Poe received "the very first words of encouragement I ever remember to have heard" in a review of his poetry by influential critic John Neal, prompting Poe to dedicate one of the poems to Neal in his second book Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems, published in Baltimore in 1829.

Poe traveled to West Point and matriculated as a cadet on July 1, 1830. In October 1830, Allan married his second wife Louisa Patterson. The marriage and bitter quarrels with Poe over the children born to Allan out of extramarital affairs led to the foster father finally disowning Poe. Poe decided to leave West Point by purposely getting court-martialed. On February 8, 1831, he was tried for gross neglect of duty and disobedience of orders for refusing to attend formations, classes, or church. He tactically pleaded not guilty to induce dismissal, knowing that he would be found guilty.

Poe left for New York in February 1831 and released a third volume of poems, simply titled Poems. The book was financed with help from his fellow cadets at West Point, many of whom donated 75 cents to the cause, raising a total of $170. They may have been expecting verses similar to the satirical ones Poe had written about commanding officers. It was printed by Elam Bliss of New York, labeled as "Second Edition", and including a page saying, "To the U.S. Corps of Cadets this volume is respectfully dedicated". The book once again reprinted the long poems "Tamerlane" and "Al Aaraaf" but also six previously unpublished poems, including early versions of "To Helen", "Israfel", and "The City in the Sea". Poe returned to Baltimore to his aunt, brother, and cousin in March 1831. His elder brother Henry had been in ill health, in part due to problems with alcoholism, and he died on August 1, 1831

Η ελληνολατρεία του Πόε - Φανατικός οπαδός και μιμητής του Βύρωνα

Η αλήθεια είναι ότι ο Πό(ε) έχει χάσει τους γονείς του από τα τρία του κιόλας χρόνια, έχει μεγαλώσει σε ξένη οικογένεια, έχει συγκρουστεί με τον θετό πατέρα του, έχει εγκαταλείψει το σπίτι του, έχει πιάσει ανεπιτυχώς διάφορες δουλειές, έχει παντρευτεί τη μόλις 13χρονη ξαδέλφη του και την έχει χάσει από φυματίωση. Ο δρόμος που βαδίζει είναι στρωμένος με αγκάθια… Αλλά διαβάζει. Διαβάζει πολύ. Αρχαία ελληνική φιλοσοφία. Ελληνική γλώσσα. Ονειρεύεται να ταξιδέψει στην Ελλάδα, να πατήσει τον βράχο, να δει την Ακρόπολη… Σε κάθε κείμενό του βρίσκει ευκαιρία να κάνει τουλάχιστον μία αναφορά στην αρχαία Ελλάδα, εισάγοντας είτε απευθείας ελληνικές λέξεις, είτε εικόνες, είτε λογοπαίγνια ονομάτων αρχαίων φιλοσόφων (Aries Tottle είναι το όνομα του φιλοσόφου που επικαλείται στο έργο του «Mellonta tauta», παραπέμποντας ευθέως στον Αριστοτέλη).

Death

On October 3, 1849, Poe was found semiconscious in Baltimore, "in great distress, and... in need of immediate assistance", according to Joseph W. Walker, who found him. He was taken to the Washington Medical College, where he died on Sunday, October 7, 1849, at 5:00 in the morning Poe was not coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition and why he was wearing clothes that were not his own. He is said to have repeatedly called out the name "Reynolds" on the night before his death, though it is unclear to whom he was referring. His attending physician said that Poe's final words were, "Lord help my poor soul". All of the relevant medical records have been lost, including Poe's death certificate.

Newspapers at the time reported Poe's death as "congestion of the brain" or "cerebral inflammation", common euphemisms for death from disreputable causes such as alcoholism. The actual cause of death remains a mystery. Speculation has included delirium tremens, heart disease, epilepsy, syphilis, meningeal inflammation, cholera, carbon monoxide poisoning, and rabies. One theory dating from 1872 suggests that Poe's death resulted from cooping, a form of electoral fraud in which citizens were forced to vote for a particular candidate, sometimes leading to violence and even murder.

Griswold's memoir

Immediately after Poe's death, his literary rival Rufus Wilmot Griswold wrote a slanted high-profile obituary under a pseudonym, filled with falsehoods that cast Poe as a lunatic, and which described him as a person who "walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayers, (never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned)".

The long obituary appeared in the New York Tribune, signed "Ludwig" on the day that Poe was buried in Baltimore. It was further published throughout the country. The obituary began, "Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it." "Ludwig" was soon identified as Griswold, an editor, critic, and anthologist who had borne a grudge against Poe since 1842. Griswold somehow became Poe's literary executor and attempted to destroy his enemy's reputation after his death.

Griswold wrote a biographical article of Poe called "Memoir of the Author", which he included in an 1850 volume of the collected works. There he depicted Poe as a depraved, drunken, drug-addled madman and included Poe's letters as evidence. Many of his claims were either lies or distortions; for example, it is seriously disputed that Poe was a drug addict. Griswold's book was denounced by those who knew Poe well, including John Neal, who published an article defending Poe and attacking Griswold as a "Rhadamanthus, who is not to be bilked of his fee, a thimble-full of newspaper notoriety". Griswold's book nevertheless became a popularly accepted biographical source. This was in part because it was the only full biography available and was widely reprinted, and in part because readers thrilled at the thought of reading works by an "evil" man. Letters that Griswold presented as proof were later revealed as forgeries.

Legacy of Edgar Allan Poe

Poe’s work owes much to the concern of Romanticism with the occult and the satanic. It owes much also to his own feverish dreams, to which he applied a rare faculty of shaping plausible fabrics out of impalpable materials. With an air of objectivity and spontaneity, his productions are closely dependent on his own powers of imagination and an elaborate technique. His keen and sound judgment as an appraiser of contemporary literature, his idealism and musical gift as a poet, his dramatic art as a storyteller, considerably appreciated in his lifetime, secured him a prominent place among universally known men of letters.

The outstanding fact in Poe’s character is a strange duality. The wide divergence of contemporary judgments on the man seems almost to point to the coexistence of two persons in him. With those he loved he was gentle and devoted. Others, who were the butt of his sharp criticism, found him irritable and self-centred and went so far as to accuse him of lack of principle. Was it, it has been asked, a double of the man rising from harrowing nightmares or from the haggard inner vision of dark crimes or from appalling graveyard fantasies that loomed in Poe’s unstable being?

Much of Poe’s best work is concerned with terror and sadness, but in ordinary circumstances the poet was a pleasant companion. He talked brilliantly, chiefly of literature, and read his own poetry and that of others in a voice of surpassing beauty. He admired Shakespeare and Alexander Pope. He had a sense of humour, apologizing to a visitor for not keeping a pet raven. If the mind of Poe is considered, the duality is still more striking. On one side, he was an idealist and a visionary. His yearning for the ideal was both of the heart and of the imagination. His sensitivity to the beauty and sweetness of women inspired his most touching lyrics (“To Helen,” “Annabel Lee,” “Eulalie,” “To One in Paradise”) and the full-toned prose hymns to beauty and love in “Ligeia” and “Eleonora.” In “Israfel” his imagination carried him away from the material world into a dreamland. This Pythian mood was especially characteristic of the later years of his life.

More generally, in such verses as “The Valley of Unrest,” “Lenore,” “The Raven,” “For Annie,” and “Ulalume” and in his prose tales, his familiar mode of evasion from the universe of common experience was through eerie thoughts, impulses, or fears. From these materials he drew the startling effects of his tales of death (“The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” “The Premature Burial,” “The Oval Portrait,” “Shadow”), his tales of wickedness and crime (“Berenice,” “The Black Cat,” “William Wilson,” “The Imp of the Perverse,” “The Cask of Amontillado,” “The Tell-Tale Heart”), his tales of survival after dissolution (“Ligeia,” “Morella,” “Metzengerstein”), and his tales of fatality (“The Assignation,” “The Man of the Crowd”). Even when he does not hurl his characters into the clutch of mysterious forces or onto the untrodden paths of the beyond, he uses the anguish of imminent death as the means of causing the nerves to quiver (“The Pit and the Pendulum”), and his grotesque invention deals with corpses and decay in an uncanny play with the aftermath of death.

On the other side, Poe is conspicuous for a close observation of minute details, as in the long narratives and in many of the descriptions that introduce the tales or constitute their settings. Closely connected with this is his power of ratiocination. He prided himself on his logic and carefully handled this real accomplishment so as to impress the public with his possessing still more of it than he had; hence the would-be feats of thought reading, problem unraveling, and cryptography that he attributed to his characters William Legrand and C. Auguste Dupin. This suggested to him the analytical tales, which created the detective story, and his science fiction tales.

The same duality is evinced in his art. He was capable of writing angelic or weird poetry, with a supreme sense of rhythm and word appeal, or prose of sumptuous beauty and suggestiveness, with the apparent abandon of compelling inspiration; yet he would write down a problem of morbid psychology or the outlines of an unrelenting plot in a hard and dry style. In Poe’s masterpieces the double contents of his temper, of his mind, and of his art are fused into a oneness of tone, structure, and movement, the more effective, perhaps, as it is compounded of various elements.

As a critic, Poe laid great stress upon correctness of language, metre, and structure. He formulated rules for the short story, in which he sought the ancient unities: i.e., the short story should relate a complete action and take place within one day in one place. To these unities he added that of mood or effect. He was not extreme in these views, however. He praised longer works and sometimes thought allegories and morals admirable if not crudely presented. Poe admired originality, often in work very different from his own, and was sometimes an unexpectedly generous critic of decidedly minor writers.

Poe’s genius was early recognized abroad. No one did more to persuade the world and, in the long run, the United States, of Poe’s greatness than the French poets Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé. Indeed his role in French literature was that of a poetic master model and guide to criticism. French Symbolism relied on his “The Philosophy of Composition,” borrowed from his imagery, and used his examples to generate the theory of pure poetry.

Poe’s Complete Works

Below is a list of the complete works of Edgar Allan Poe.

Click on a title to read the full text.

Short Stories

The Angel of the Odd

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket

The Assignation (The Visionary)

The Balloon Hoax

Berenice

The Black Cat

Bon-Bon (The Bargain Lost)

The Cask of Amontillado

The Colloquy of Monos and Una

The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion (The Destruction of the World)

A Decided Loss (Loss of Breath)

A Descent into the Maelström

The Devil in the Belfry

Diddling Considered as One of the Exact Sciences

The Domain of Arnheim (The Landscape Garden )

The Duc de L’Omelette

Eleonora

Epimanes (Four Beasts in One) (The Homocameleopard)

The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar

The Fall of the House of Usher

The Gold-Bug

Hans Phaall — A Tale (The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall)

Hop-Frog

How to Write a Blackwood Article (The Psyche Zenobia)

The Imp of the Perverse

The Island of the Fay

King Pest

Landor’s Cottage

Ligeia

The Light-House

Lionizing

The Literary Life of Thingum Bob, Esq

The Man of the Crowd

The Man that was Used Up

The Masque of the Red Death

Mellonta Tauta

Mesmeric Revelation

Metzengerstein

Morella

Morning on the Wissahiccon (The Elk)

MS. found in a Bottle (Manuscript found in a Bottle)

The Murders in the Rue Morgue

The Mystery of Marie Roget

Mystification (Von Jung)

Never Bet the Devil Your Head

The Oblong Box

The Oval Portrait (Life in Death)

Peter Pendulum, the Business Man

The Pit and the Pendulum

Politian

The Power of Words

The Premature Burial

The Purloined Letter

The Scythe of Time

Shadow — A Fable

Silence — A Fable (Siope — A Fable)

Some Words with a Mummy

The Spectacles

The Sphinx

The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether

A Tale of Jerusalem

A Tale of the Ragged Mountains

The Tell-Tale Heart

Thou Art the Man

The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade

A Succession of Sundays (Three Sundays in a Week)

Von Kempelen and His Discovery

Why the Little Frenchman Wears His Hand in a Sling

William Wilson

X-ing a Paragrab

Poems

An Acrostic (From an Album)

Al Aaraaf

Alone (From an Album Alone) (“From childhood’s hour I have not been…“)

Annabel Lee

Bridal Ballad (Song of the Newly-Wedded)

The Bells

Beloved Physician

Catholic Hymn

The Coliseum

The Conqueror Worm

The Divine Right of Kings

The Doomed City (The City in the Sea)

A Dream

Dream-Land

Dreams

A Dream Within a Dream

Eldorado

Elizabeth

Eulalie

Evening Star

Fairyland

Fanny

For Annie

The Happiest Day

The Haunted Palace

Imitation

Impromptu [To Kate Carol]

Irene (The Sleeper)

Israfel

The Lake

Latin Hymn

Lenore

[Lines on Joe Locke]

Lines Written in an Album (To Elizabeth) (To F——s S. O——d)

O, Tempora! O, Mores!

A Paean

Preface (Romance)

The Raven

Serenade

Song of Triumph

Sonnet (An Enigma)

Sonnet — Silence

Sonnet — To Science

Sonnet — To Zante

Spiritual Song

Stanzas (“In youth I have known one…”)

Stanzas [To F. S. O.]

Tamerlane

To — (“The bowers whereat …”)

To —— (“Sleep on, sleep on, another hour …”)

To — (Song)

To Helen (“Helen, thy beauty is to me…”)

To Helen (“I saw thee once — once only…”)

To Her Whose Name is Written Below (A Valentine)

To M— (Alone) (“O! I care not that my earthly lot…”)

To M. L. S

To Margaret

To Mary (To One Departed )

To Marie Louise

To My Mother

To One in Paradise (To One Beloved), (To Ianthe in Heaven)

To ——[Violet Vane]

Ulalume

Spirits of the Dead

The Valley of Unrest (The Valley Nis)

Spirits of the Dead

BY EDGAR ALLAN POE

I

Thy soul shall find itself alone

’Mid dark thoughts of the gray tombstone—

Not one, of all the crowd, to pry

Into thine hour of secrecy.

II

Be silent in that solitude,

Which is not loneliness—for then

The spirits of the dead who stood

In life before thee are again

In death around thee—and their will

Shall overshadow thee: be still.

III

The night, tho’ clear, shall frown—

And the stars shall look not down

From their high thrones in the heaven,

With light like Hope to mortals given—

But their red orbs, without beam,

To thy weariness shall seem

As a burning and a fever

Which would cling to thee for ever.

IV

Now are thoughts thou shalt not banish,

Now are visions ne’er to vanish;

From thy spirit shall they pass

No more—like dew-drop from the grass.

V

The breeze—the breath of God—is still—

And the mist upon the hill,

Shadowy—shadowy—yet unbroken,

Is a symbol and a token—

How it hangs upon the trees,

A mystery of mysteries!

Source: The Complete Poems and Stories of Edgar Allan Poe (1946)

Σχόλια